Contents

- Understanding the Limitations of the BCG Matrix

- BCG Limitation 1: The Market Attractiveness Metric is Too Simplistic

- BCG Limitation 2: Competitive Position is Too Simplistic

- Limitation 3 = There is Only Ever ONE Star or Cash Cow in Any Market

- Limitation 4 = It Assumes that Cash Cows are “Protected”

- Limitation 5 = Many Dogs Make Good Money

- Limitation 6 = Designed as a Portfolio Investment Tool for Large Conglomerates

- Limitation 7 = Underlying Assumption that Firms Could Develop a Cost Leadership Position

- Limitation 8 = Market Growth Rate Depends upon the Market Definition

- Limitation 9 = The Matrix is NOT Designed to Plot Individual Products

- Limitation 10 = Terms Can Be Misleading

- Limitation 11 = Portfolios Need to Fit Neatly into a Clear Quadrant

- Limitation 12 = It is Just a Conceptual Model

Understanding the Limitations of the BCG Matrix

Why Does the BCG Matrix have Limitations?

Although the BCG (Boston Consulting Group) matrix is a widely used strategic model and is still discussed in many strategy and marketing textbooks, it does carry significant practical limitations.

This is because it is a model that was developed in the late 1960s, primarily to assist large-scale conglomerates to make investment portfolio decisions for their strategic business units (SBUs).

However, overtime the matrix has been adapted to also be used as a strategy planning tool, with general strategic guidance for businesses that are placed in the different quadrants of the BCG matrix.

Therefore, due to the combination of the age of the model, its initial design and intent, and its modification of usage over time – the BCG matrix has many limitations in practical use, as will be outlined below.

You can review the below article, or alternatively you can review the summary video.

Summary List of BCG Matrix Limitations

- Market Attractiveness is Too Simplistic

- Competitive Position is Too Simplistic

- There is Only Ever ONE Star or Cash Cow in Any Market

- It Assumes that Cash Cows are “Protected”

- Many Dogs Make Good Money

- Designed as a Portfolio Investment Tool for Large Conglomerates

- Underlying Assumption that Firms Could Develop a Cost Leadership Position

- Market Growth Rate Depends upon the Market Definition

- The Matrix is NOT Designed to Plot Individual Products or Brands

- Terms Can Be Misleading

- Needs to Fit Neatly into a Clear Quadrant

- It is Just a Conceptual Model

BCG Limitation 1: The Market Attractiveness Metric is Too Simplistic

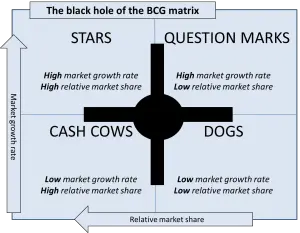

On the vertical axis on the matrix (one of the two dimensions used) is market growth rate percentage. This is a proxy measure for the overall attractiveness of the market that the business is competing in.

This means that the only assessment of market attractiveness used in the model is market growth rate, where it is assumed that a fast-growing market is an attractive market to enter. While this is a favorable attribute of any market, it is only one assessment criteria that a business should be using.

There are many other considerations that should be taken into account when assessing the overall attractiveness of the market, especially for strategy purposes. Some of these factors would include:

- The overall market size

- Profit margins of products in the market

- The degree of competitive rivalry

- The potential threat of disruption

- Cost of growing market share and being competitive

- Long-term technology/R+D costs

- The amount of ongoing innovation required

- Bargaining power of channel partners

- Likelihood of marketing environmental changes

- The impact of government regulation

Relying upon a single metric (in this case, market growth rate) is too simplistic and ignores an overall assessment of the attractiveness of a market. This is most likely to lead to errors in the assessment of market’s attractiveness, in turn leading to poor strategy decisions.

Companies choosing to work with the BCG matrix would need to broaden the assessment of market attractiveness beyond just market growth rate and include some of the factors listed above.

BCG Limitation 2: Competitive Position is Too Simplistic

A similar limitation applies to the second dimension used in the BCG matrix. On the horizontal access is relative market share, which is being used as a proxy measure for overall competitive strength.

This assumption has some underlying logic to it, as market share position is an indicator of competitive performance and overall market strength

For example, relative market share could be a reasonable measure of competitive strength in a low growth market (that is, for the cash cows and the dogs), but it is far less effective in the high-growth markets, where the competitive situation (and therefore market shares) are far more dynamic.

However, it should be noted that relying upon current market share only, especially for an early-stage market (for Stars and for Question Marks) could also be misleading and only reflective of timing of entry into the market.

That is, an early market entry player would have a higher market share than a late entry company, especially when the market was still in its introduction and/or early growth phase of its product lifecycle.

The biggest concern with the relative market share metric is that there are other factors that also need to be considered when forming a view of overall competitive position and strength. This is because market share alone takes no account of the underlying strengths, capabilities, and resources of the firm.

If we were to fully assess market strength, then we would need to include some of the following factors:

- The overall strength of our brand

- The level of customer loyalty

- Whether we are able to implement premium pricing

- Our degree of innovation skills and capability

- Our product differentiation

- The extent of our product lines and overall product mix

- Established retailer relationships

- Our bargaining power with our channel partners

- Financial and other resources

- Logistics and distribution advantages

- Propriety designs and patents

- Any interrelated products and/or businesses that we can leverage

- Our level of market knowledge, through data analytics and other sources

Apple as a Dog

Adding to the above two limitations, as discussed both the axis (dimensions) used in the BCG matrix to form the quadrants are very limited top-level, or ballpark, estimations of market attractiveness and competitive position. As a result, the placement of businesses within these quadrants is prone to substantial error.

For example, as will be discussed further below, the iPhone division of Apple would be classified as a “dog” in the BCG matrix, because on relative unit market share it is below Samsung. Logic will tell you that classifying the iPhone business of Apple as a dog is not correct, as it is an extremely profitable operation.

This misclassification occurs because of the simplicity of the two axes/dimensions used to construct the quadrants in the BCG.

These First Two Limitations Stem from a Key Benefit of the BCG Matrix

Before continuing on to the other limitations, it is important to highlight that it is the overall simplicity of the BCG matrix – that you only need to rely upon two easy-to-formulate metrics – that makes it memorable and still in use after so many years.

In other words, these first two concerns with the BCG matrix actually stem from the model’s biggest advantage, which is its overall simplicity. It is this strength of simplicity that creates its weakness of overall accuracy, as these two measures are too simplistic and narrow for the purpose of what they are trying to measure and identify.

Limitation 3 = There is Only Ever ONE Star or Cash Cow in Any Market

In the original design of the BCG matrix, which was primarily structured for large-scale conglomerates operating in manufacturing industries, there could only ever be ONE Star or Cash Cow in any market.

This occurs because the horizontal metric is Relative Market Share. This is calculated by dividing the firm’s unit market share by their largest competitor.

For example, 40% (our firm, the market leader) divided by 20% (our largest competitor) = 2.0 relative market share. That calculation places us in either the Star or Cash Cow quadrant (depending upon market growth rate).

And our firm would be the only Star or Cash Cow in our industry. All other players in the industry would have their market share divided by our market share, as we are the market leader, and therefore their largest competitor.

For example, our largest competitor above, would have a relative market share of 20% divided by 40% = 0.50. Likewise, smaller competitors will also have their market share divided by our market share resulting in even a smaller result – clearly placing all of them either in the Question Mark or Dog quadrants (again, depending upon market growth rate).

This occurs because the underlying principle of the BCG matrix in its original construction was that there was a substantive cost advantage to being the unit market share leader. This is because you could derive economies of scale and substantial experience curve benefits.

Both of these factors work together to ensure that your average cost of production per unit was substantially lower than your competitors. This gave you the dual advantages of both higher profit margins and lower prices in the market, which in turn would drive increases in your market share position.

However, in today’s marketplace, many markets are not as price-sensitive and being leader on price is not necessarily the best strategy.

For example, as mentioned above, Apple would be classified as a dog in the matrix, as they have a lower unit market share than Samsung in the smart phone market. However, Apple competes with: product innovation, brand loyalty, customer following, retail presence, media and publicity, proprietary designs and software, interrelated products, and so on.

Therefore, classifying Apple as a dog simply because they have a lower relative market share is illogical. They make substantial profits from their iPhones and will continue to do so well into the future. In reality, they are Cash Cows for the business.

Referring back to limitation number 2 above, if the matrix had a better assessment of overall relative market strength (not just relying upon market share position) then it is likely that iPhones would be classified as a cash cow for Apple.

Alternatively, if the relative market share metric is desired to be maintained then there is a good argument that the division of quadrants should be altered. That is, rather than the vertical line splitting the quadrants and a relative market share of 1.0, then that cut-off point should be lowered to 0.50 or even perhaps 0.33.

If the BCG matrix was produced with a lower cut-off threshold for the split of cash cow/dogs and stars/question marks, then multiple businesses could be classified more appropriately as a superior portfolio – that is Apple iPhones would become a cash cow on the model, which is more appropriate.

Limitation 4 = It Assumes that Cash Cows are “Protected”

There is no doubt that the BCG matrix views cash cows as the superior quadrant, as this is the prime profit generating quadrant for businesses. Businesses classified as cash cow will make superior profits that can be reinvested into stars and potentially question marks.

And building upon limitation 3 above, the BCG matrix has an assumption that cash cows are relatively protected. That is, it is very hard to erode the competitive position of a cash cow as they operate in a low growth/mature market.

This point is interrelated with the product lifecycle in marketing, where competitive behavior and its impact tends to dampen in mature markets. This is because substantial changes in the market share are more challenging in maturity, as opposed to the introduction and growth phases of the product lifecycle.

This has underlying logic to it because, in a mature market, customer loyalty and habitual purchases are far more established than in a growth market. And this is why in the maturity phase of the product lifecycle we tend to see more stable market shares.

For example, if McDonald’s holds 40% of the fast-food market in a country this year, then it is likely that they will have a similar market share next year, and beyond, and potentially 10 years into the future.

The BCG matrix assumes that this competitive position is almost guaranteed because the firm has superiority in market share, delivering a cost advantage, delivering an unbeatable pricing and profit margin strategy in the marketplace.

However, most markets are far more dynamic than they were in the late 1960s when the BCG matrix was developed. There are frequent changes to the marketing environment and consumer lifestyles have changed substantially and there has been a shift from mass marketing to target marketing and even to niche marketing.

We have particularly seen the impact of that in the Internet era, since the mid-90s. We have seen the emergence of large substantial companies, such as Amazon, Facebook, Google – at the expense of established organizations.

For example, in most countries, large newspapers were once superior cash cows for advertising for employment roles and real estate. However, most of these players have been overtaken by Internet start-ups.

Likewise, there are many large organizations that were once clear cash cows and dominated their markets in terms of relative market share – such as Kodak, Blockbuster and Toys R Us – each of these are now either out of business or are a fraction of their former substantial businesses.

This means that the BCG matrix may provide misleading reassurance to large companies if they are classified as cash cows in the matrix. This does not lead to a long-term protected position without working hard to evolve and adapt to the changing environment.

This false reassurance could lead to a degree of either corporate arrogance or corporate inaction, as the business sees themselves as the rightful market leader because of their superior market share position. In this regard, the BCG matrix could provide unhelpful strategic reassurance and information.

Limitation 5 = Many Dogs Make Good Money

The general advice for a business classified as a dog is to either divest the business operation, or at least not support it with any resources. The rationale behind this, according to the BCG matrix, is that this business has limited/no growth potential.

As it has limited market share in a mature/low growth market, there is little it can do to grow market share. In other words, the matrix implies that without the ability to build market share, the portfolio has limited value.

However, as emphasized by the Apple example above, this is also potentially quite misleading. Many business portfolios classified as dogs in the matrix will be in fact very profitable. Some marketing and strategy textbooks will refer to these portfolios as “cash dogs”.

While they are less likely to make the substantial profits of the cash cow, they are nonetheless valuable portfolios in their own right. And the strategic guidance provided by the matrix of providing them with limited support and resources, may not be an overly helpful strategic suggestion.

Like with cash cows, cash dogs would need to be supported as well in order to maintain their competitive position and ensure their long-term profitability over time.

Indeed, as highlighted above in limitation 2, there are multiple factors contributing to competitive strength and performance in the marketplace. Therefore, ruling out a portfolio for support simply because it has a lower market share than the market leader, may neglect the substantial advantages of the business.

It could be very possible for a business with a relatively low market share, but with substantial competitive advantages, to significantly increase their profitability over time and even generate profits that rival some cash cows.

Limitation 6 = Designed as a Portfolio Investment Tool for Large Conglomerates

The history and the purpose of the BCG matrix needs to be remembered when assessing its suitability for use.

It was initially designed for use by a single company, typically a large conglomerate primarily operating in manufacturing sectors, where they would plot their various, and often unrelated, business portfolios (or strategic business units = SBUs) onto one simplified graph format and be able to compare them on a side-by-side basis.

Therefore, the original intention of the BCG matrix was to identify how the available resources of the overall organization should be allocated across the relative business units.

A common outcome of the BCG matrix was to recommend that the surplus cash generated by the business portfolios classified as cash cows should be allocated to stars and potentially to question marks.

And while this was the original intention, over time various strategy and marketing textbooks have included the matrix in chapters on strategy development and have modified the intention of some the quadrants. And it was not designed as a competitive comparison tool either, even though it can be utilized in that fashion.

However, given its relatively narrow focus and purpose, along with the various other limitations listed in this article, it would be concerning if strategy development relied upon the BCG matrix only. It needs to be used in conjunction with other strategic planning tools and information.

Limitation 7 = Underlying Assumption that Firms Could Develop a Cost Leadership Position

This point has been touched upon in the other limitations above. A central underpinning of the BCG matrix is that a cost leadership position is the most superior strategy you can implement in the market.

It is somewhat related to Porter’s Generic Strategies, where cost leadership is a paramount strategy and differentiation and/or focus is pursued only if cost leadership is unavailable.

Typically, it was believed that only one firm could achieve true a cost leadership position in the same market. An example in today’s market would be Walmart supermarkets, which has a cost advantage over many other competitors.

However, as mentioned in limitation 2 above, there are multiple approaches to competitive strategy in today’s marketplace. Remember that the BCG matrix was developed in the 1960s, where economies were far more manufacturing based. Today we operate in economies that are highly services oriented and consumers have far more disposable income. This means that price competition is probably less relevant than it was in the 1960s.

This creates two concerns with the BCG matrix with this point. The first is that cost leadership may not be a superior competitive strategy – as per the Apple example above, and the various strategic factors listed in limitation 2 above.

And the second concern is whether a true cost advantage can be achieved in many services industries. Certainly, Walmart have achieved that position in supermarkets, but that was after substantial investment in logistics, distribution, in-store design and technology, and many other factors.

However, in many industries, it may not be possible to obtain a cost advantage strong enough to leverage in the marketplace – which would make it uncertain for the business if that portfolio could become a cash cow with all the benefits suggested by the BCG matrix.

Limitation 8 = Market Growth Rate Depends upon the Market Definition

One of the key strategic decisions for any business is “what market are we competing in?” In answering this question, the business defines the market for themselves.

For example, is McDonald’s in the burger market, or are they in the fast-food market, or are they in the eat-out-of-home market (which would include restaurants and cafés). Not only does the definition of a market influence their strategy, their set of direct and indirect competitors, but it would also impact the market growth rate used in the BCG matrix.

For instance, the burger market for McDonald’s may have a market growth rate of 2%, whereas the eat-out-of-home market could have a market growth rate of 15%. Depending upon the growth rate percentage utilized in this case, the business portfolio would be classified into different quadrants – and would then suggest different resource allocations and strategy directions.

As another example, should Apple define its phone market as all mobile phones or smart phones only? Apple only competes in the smart phone sector, but most other mobile phone manufacturers compete in both smart and non-smart phone sub-markets.

Given that the smart phone market has a higher growth rate and Apple has a higher market share in that market, Apple would potentially classify their phone business as a “star” – but if they considered the overall mobile market instead, it would be more likely to classify their phone business as a “dog”, because the market is more mature and they have less market share of the total combined market.

Therefore, what is the most appropriate approach for a firm to use? That is more of a strategic question and would impact many significant business decisions in the portfolio. But it is clear that the answer will influence where the portfolio is allocated in the BCG’s four quadrants.

Limitation 9 = The Matrix is NOT Designed to Plot Individual Products

As discussed, the original intent of the BCG matrix was for use by large conglomerates assessing their own business investment and to allocate investment funds accordingly.

However, over time the BCG matrix has evolved through usage to plot individual brands and sometimes even individual products. There is a concern therefore, that the strategic outcomes of plotting individual products will not be appropriate.

For instance, a firm with a large product range plotting individual products onto the BCG matrix will probably identify that they have a mix of cash cows and a lot of dogs in one mature market. And then in another market, which is growing, they have a mix of stars and question marks.

In terms of the BCG matrix usage, ideally we need a balanced portfolio where we do not have too many question marks to support, if any at all. Therefore, an attractive product mix in a growth market may be plotted as a looming liability when using the BCG matrix.

In reality, related products in a product line to not carry the same requirement for investment as does a complete business portfolio (SBU) that is struggling to gain market share overall. So while the BCG matrix is helpful in terms of direction for a business, often its recommendations are not suitable for individual products or brands.

This is because the overall product offering and extended product line should work in synergy to deliver profitability and strong brand equity. Therefore, care needs to be taken when plotting individual brands or products onto the matrix.

Limitation 10 = Terms Can Be Misleading

One of the “advantages” of the BCG matrix is that it uses unusual terms – stars, cash cows, etc. – which makes the model quite memorable. In fact, many students will recall this model long after their studies, because of the terminology used.

However, the actual terms can be misleading and open to misinterpretation. We have already touched upon dogs above, in limitation 5, when many dogs could be quite profitable. But the term “dogs” in the BCG matrix tends to have a negative connotation. While this may be acceptable in some situations, it is misleading overall.

Likewise, the term “stars” tends to suggest that this is the best portfolio you can have. In reality, stars are future/potential cash cows – provided we support them adequately and we successfully managed their competitive position.

In other words, stars require substantial investment and are most likely to be a drain on financial resources. While they will deliver substantial long-term profits, in the short term we need to find money to invest in them. A good example here would be Amazon, which made limited profits in its first 20 years or so of its operations.

And if we do not manage them correctly and our competitive position is eroded, then stars can deteriorate into question marks and then finally into dogs – there is no guarantee of long-term success, even though they are currently well placed.

And as discussed above in limitation 4, cash cows are not guaranteed and protected forever. While cows, in real life, provide milk every day, eventually they will run out of ability to produce quality and quantity of milk. The same thing will happen to our cash cow businesses, and eventually they will dry up as well – as per the Kodak and Toys “R” Us examples above.

And finally, question marks are often misunderstood in the matrix. The true question to ask of portfolios in this quadrant is why should we continue to invest in them? And are we better off divesting them?

This because question marks require far more reinvestment than stars do but have no guarantees of being anything more than a long-term dog. In other words, we could lose a lot of money by supporting a question mark that does not have a valid reason for long-term success – that is, have superior competitive advantages irrespective of its current relative market share position.

Limitation 11 = Portfolios Need to Fit Neatly into a Clear Quadrant

The BCG matrix works best if the business portfolios considered are classified clearly into one of the quadrants. However, if a business portfolio is classified somewhere in the middle, then the matrix has no obvious suggestion for strategy or investment.

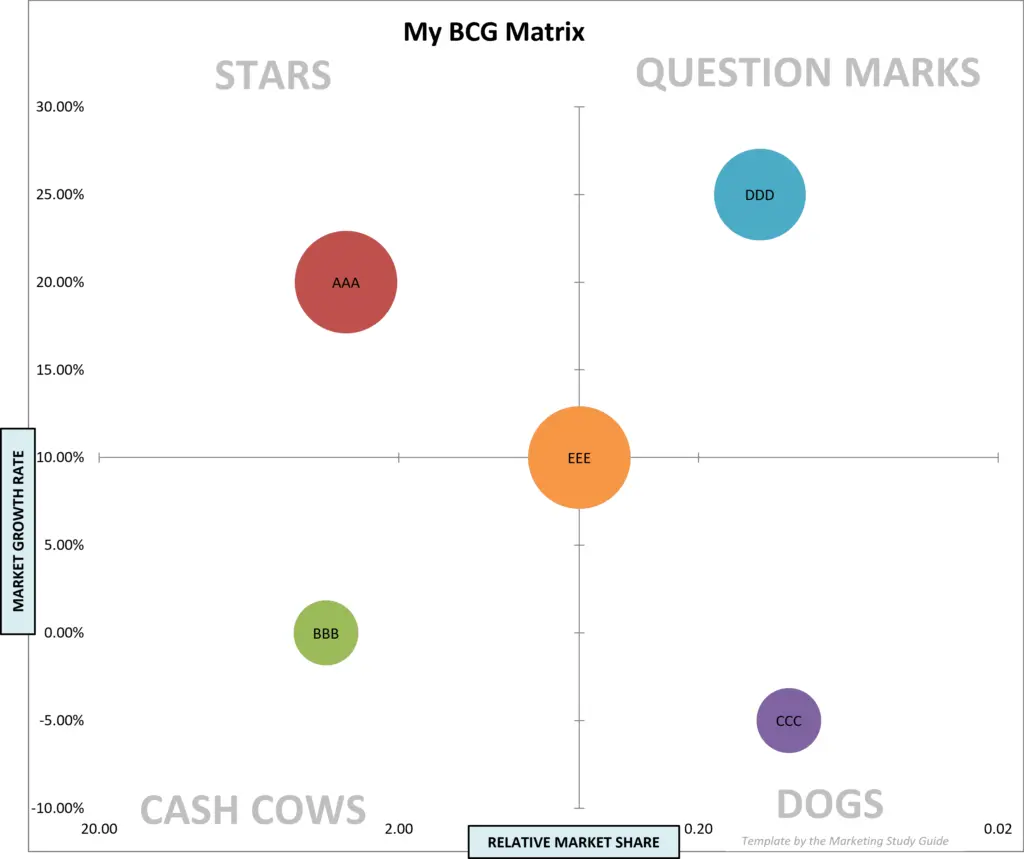

For example, a business with a relative market share of 1 (equal market leader) in a moderate growth market of 10%, would be classified right in the middle of the BCG matrix. This means that it would be ¼ each of stars, question marks, cash cows and dogs – not a helpful classification.

We could refer to this as the “black hole” of the BCG matrix, and this situation would not be uncommon to any strategic matrix tool. In many regards, they all require businesses or situations to be classified quite neatly. For example, the product lifecycle needs markets classified as either growth or maturity for ease-of-use and strategy direction.

As shown in the diagram, any business portfolios classified into the black areas of the BCG matrix really would find no guidance or help from the model – other than interpreting half-and-half a cash cow/star, or other configuration. In this case, you would most likely be better off using a different strategic tool.

Limitation 12 = It is Just a Conceptual Model

Like most models and frameworks within textbooks, the BCG matrix is just a conceptual model. It has some very helpful ideas and some good principles of strategy underpinning it.

However, as indicated in this article, it also has substantial limitations which limit the effectiveness of its use.

Regardless, we need to keep in mind that all models and concepts that we come across in textbooks provide a form of guidance that help inform our decision. They are not designed to be the sole arbitrator of our strategy.

You should think of the BCG matrix outcomes as “suggestions”, rather than firm recommendations. In this regard, the BCG matrix should be beneficial in guiding strategy development, particularly of a more complex portfolios and/or product lines.

Related Articles